Serial Dilution

A dilution is a reduction in the concentration of a solution. A serial dilution is a series of repeated dilutions that provides a geometric dilution of the original solution. This is commonly performed in experiments that involve concentration curves on a logarithmic scale. Serial dilutions are used extensively in biochemistry and microbiology. If you are wondering how to do serial dilutions, this serial dilution calculator is the tool for you.Here, we provide you with every imaginable piece of information regarding serial dilutions; from calculations for the required volume of solution at the end of each dilution, to the exact amount of stock solution and dilutant needed to make the first solution, to the dilution factor of the.

Problem #1: The following successive dilutions are applied to a stock solution that is 5.60 M sucrose:

Solution A = 46.0 mL of the stock solution is diluted to 116 mL

Solution B = 58.0 mL of Solution A is diluted to 248 mL

Solution C = 87.0 mL of Solution B is diluted to 287 mL

What is the concentration of sucrose in solution C?

Solution: (the solution will be followed by some discussion)

1) Assign unknowns to the final molarities of each dilution:

molarity of solution A = x

molarity of solution B = y

molarity of solution C = z

2) Set up all three dilutions using M1V1 = M2V2

Solution A ⇒ (5.60) (46) = (x) (116)

Solution B ⇒ (x) (58.0) = (y) (248)

Solution C ⇒ (y) (87.0) = (z) (287)

3) Each of these three eqations may now be solved in turn to give the final answer (symbolized by the variable z):

Solution A ⇒ (5.60) (46) = (x) (116)x = 2.2207 M

Solution B ⇒ (2.2207) (58.0) = (y) (248)

y = 0.51936 M

Solution C ⇒ (0.51936) (87.0) = (z) (287)

z = 0.157 M (this is the final answer)

Advice: if you use the above technique, make sure to carry several guard digits as you do each calculation. In the above, I carried two guard digits in my values for x and y.

I would like to now reconsider the solution. In place of the specific numbers in step two, I would like to use symbols:

Solution A ⇒ (Ci) (V1) = (x) (V2)Solution B ⇒ (x) (V3) = (y) (V4)

Solution C ⇒ (y) (V5) = (Cf) (V6)

x and y = intermediate concentrations

Ci = initial concentration

Cf = final concentration

I'm now going to form one equation that relates Ci and Cf. To do this, I will eliminate the intemediate concentrations symbolized by x and y. First x:

(Ci) (V3 Fold Serial Dilution Numbers

1) = (x) (V2)x = (Ci) (V1 / V2)

Now, substitue into the equation for solution B:

(Ci) (V1 / V2) (V3) = (y) (V4)y = (Ci) (V1 / V2) (V3 / V4)

Now, substitue into the equation for solution C:

(Ci) (V1 / V2) (V3 / V4) (V5) = (Cf) (V6)(Ci) (V1 / V2) (V3 / V4) (V5 / V6) = Cf

Let's see if it works:

Cf = (5.60) (46 / 116) (58 / 248) (87 / 287)Cf = 0.157 M

Hey! It works!

Notice that each volume ratio represents a dilution. Consequently, each volume ratio is a factor less than 1.

Problem #2: What is the molarity of dilution 1?

1) A stock solution of salicylic acid is diluted by transferring 10.0 mL of the stock solution into a beaker and adding 40.0 mL of water. The beaker is labeled dilution 1.2) 5.00 mL of the solution in the beaker labeled dilution 1 is transferred to another beaker and 15.0 mL of water is added. The beaker is labeled dilution 2.

3) 5.00 mL of the solution in the beaker labeled dilution 2 is transferred to another beaker and 15.0 mL of water is added. The beaker is labeled dilution 3.

4) 1.00 mL of the solution in the beaker labeled dilution 3 is transferred over to another beaker called dilution 4 and enough water is added so that the final volume is 5.00 mL and the concentration of the final dilution is 2.10 x 10-6 M.

Solution:

1) from dilution 4 to dilution 3:

(x) (1.00 mL) = (2.10 x 10-6) (5.00 mL)x = 1.05 x 10-5 M (concentration of dilution 3)

2) from dilution 3 to dilution 2:

(x) (5.00 mL) = (1.05 x 10-5 mol/L) (20.0 mL)x = 4.20 x 10-5 M (concentration of dilution 2)

3) from dilution 2 to dilution 1:

(x) (5.00 mL) = (4.20 x 10-5mol/L) (20.0 mL)x = 1.68 x 10-4 M (concentration of dilution 1)

4) from dilution 1 to the stock:

(x) (10.00 mL) = (1.68 x 10-4mol/L) (50.0 mL)x = 8.40 x 10-4 M (concentration of the stock solution)

Note how the problem is worded to avoid giving a final volume. It simply tells you the starting volume (5.00 mL in 2 and 3) and that 15.0 mL was added. Nowhere does it state that the solution was diluted to 20 mL. Also, note the implicit assumtion that the volumes are additive. This is a resonable assumption in this example.

Here is a repeat of the combined equation from above:

(Ci) (V1 / V2) (V3 / V4) (V5 / V6) = Cf

Since there are four dilutions in Problem #2, I will add another volume term:

(Ci) (V1 / V2) (V3 / V4) (V5 / V6) (V7 / V8) = Cf

Since we are interested in Ci, let us move all the volume terms to the other side:

Ci = (Cf) (V2 / V1) (V4 / V3) (V6 / V5) (V8 / V7)

Now, let us insert values into the revised equation (please note that all even subscripts are the final molarity and the odd subscripts are the starting molarity):

Ci = (2.10 x 10-6) (50 / 10) (20 / 5) (20 / 5) (5 / 1) = 8.40 x 10-4 M

Problem #3: You have prepared 10 mL of a stock solution of 1.000 M hydrochloric acid, HCl. You serially dilute the stock solution 3 times, such that each step of the serial dilution dilutes the original solution by 1/2. What will the final concentration be in the final test tube?

Solution #1:

Start with 10 mL of 1 M solution (I'll ignore sig figs for the moment).Take the 10 mL of solution and add 10 mL of water. The solution is now 20 mL of 0.5 M.

Take the 20 mL of solution and add 20 mL of water. It's now 40 mL of 0.25 M.

Take the 40 mL of solution and add 40 mL of water. It is now 80 mL 0.125 M.

So, the final concentration is 0.125 M.

Note how the concentration is cut in half each time the total volume doubles.

Solution #2:

This is a cleaned up version of the answer I copied from Yahoo Answers:

OK, so you're starting with 10 mL of 1 M solution and you're diluting it by half.So take 5 mL of solution and add 5 mL of water, the solution is now 0.5 M.

Take 5 mL of that and add 5 mL of water. It is now 0.25 M

Take 5 mL of that and add 5 mL of water. It is now 0.125 M.

The final concentration is 0.125 M.

Note how only the stock solution is used as well as half of each diluted solution in each step. This is the correct way to do this type of dilution in the lab. If you spill a solution in a given step, you can return to the solution of the previous step and continue (after you clean up the spill!).

I did not use any of the notation used in Problems #1 and #2. I will leave that as an exercise to the reader.

The above type of dilution is called a two-fold dilution. In a two-fold dilution, the volume of the original solution is always doubled, as in going from 1 to 2.

A three-fold dilution would be a tripling of the solution volume, as in going from 1 to 3.

Although not a serial dilution, the below is an example of a two-fold dilution.

Problem #4: To make a two-fold dilution of 10 mL of solution, what amount of solvent would you use and how would you do this?

3 Fold Serial Dilution Calculations

To perform a dilution you can always use the equation:(Volume of solution)/(vol of solution + vol of solvent)

Since it is a two-fold dilution, you use the same volume of solvent as you have of solution.

In this case, you just add ten milliliters:

(10)/(10 + 10) = 1/2 ---> a 1 to 2 dilution (also called two-fold).

If this was a three-fold dilution, we would have this: (10)/(10 + 20) = 1/3 ---> a 1 to 3 dilution (also called three-fold).

Problem #5: To prepare a very dilute solution, it is advisable to perform successive dilutions of a single prepared reagent solution, rather than to weigh out a very small mass or to measure a very small volume of stock chemical. A solution was prepared by transferring 0.661 g of K2Cr2O7 to a 250.0-mL volumetric flask and adding water to the mark. A sample of this solution of volume 1.000 mL was transferred to a 500.0-mL volumetric flask and diluted to the mark with water. Then 10.0 mL of the diluted solution was transferred to a 250.0-mL flask and diluted to the mark with water.

(a) What is the final concentration of K2Cr2O7 in solution?

(b) What mass of K2Cr2O7 is in this final solution?

Solution:

1) Calculate the molarity of the first solution thusly:

MV = mass / molar mass(x) (0.2500 L) = 0.661 g / 294.181 g/mol

x = 0.008987664 M (I won't round off very much until the end.)

2) Now, use this for the first dilution (1.000 mL to 500.0 mL):

M1V1 = M2V2(0.008987664 mol/L) (1.000 mL) = (x) (500.0 mL)

x = 0.000017975328 M

3) Use M1V1 = M2V2 again for the second dilution (10.00 mL to 250.0 mL):

(0.000017975328 mol/L) (10.00 mL) = (x) (250.0 mL)x = 0.00000071901312 M

Rounded to four sig figs, it is 0.0000007190 M (the answer to part (a) of the question)

4) Lastly, use MV = mass / molar mass to get the mass of K2Cr2O7 in the final 250 mL of solution.

(0.00000071901312 mol/L) (0.2500 L) = x / 294.181 g/molx = 0.00005288 g (or, if you prefer 5.288 x 10-5 g)

This answer to part (b) gives the amount that would have had to have been weighed out if the solution had been prepared directly.

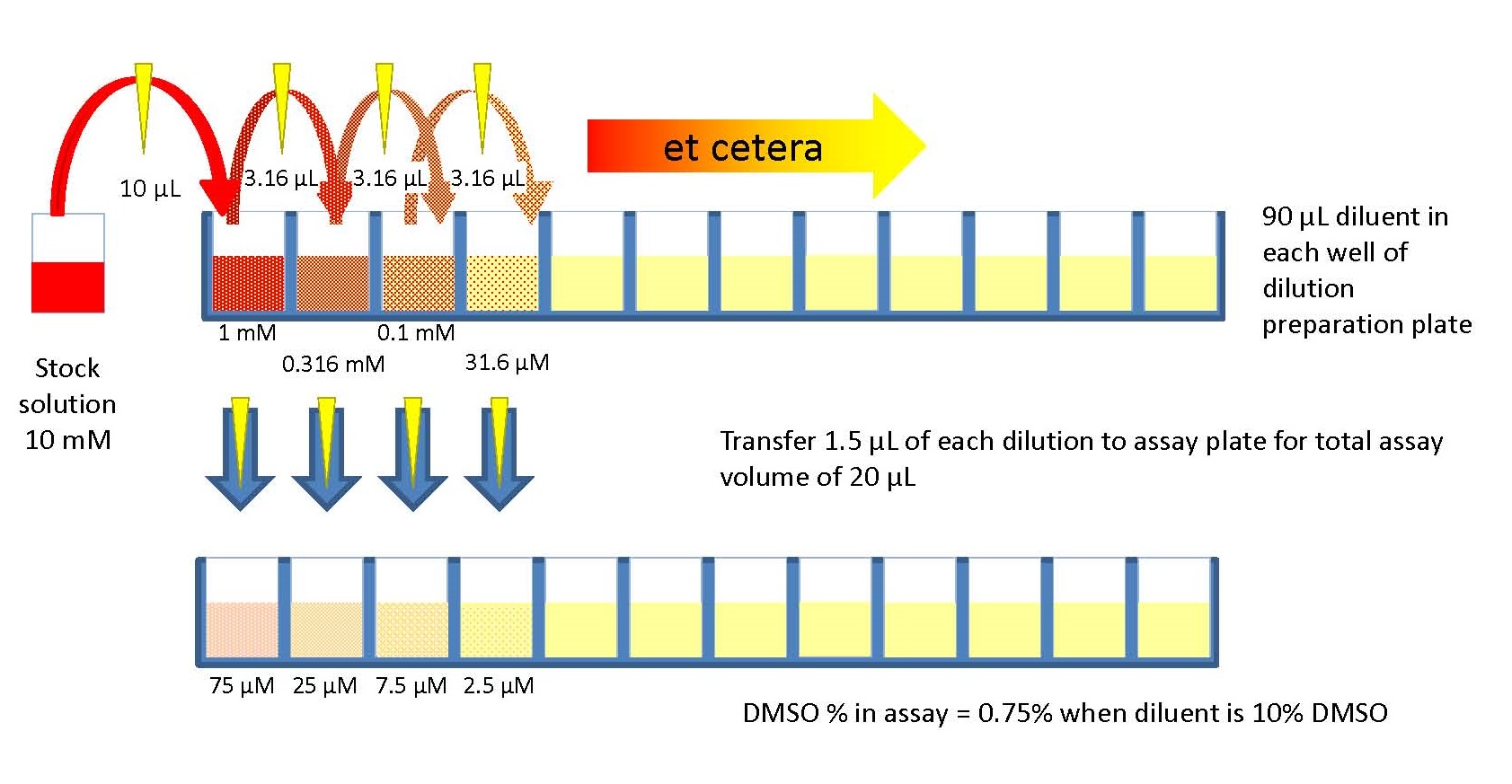

This section is not a recipe for your experiment. It explains someprinciples for designing dilutions that give optimal results. Onceyou understand these principles, you will be better able to designthe dilutions you need for each specific case.

Often in experimental work, you need to cover a range ofconcentrations, so you need to make a bunch of differentdilutions. For example, you need to do such dilutions of thestandard IgG to make the standard curve in ELISA, and then againfor the unknown samples in ELISA.

You might think it would be good to dilute 1/2, 1/3, 1/10, 1/100.These seem like nice numbers. There are two problems with this series ofdilutions.

- The dilutions are unnecessarily complicated to make. You need to do a differentcalculation, and measure different volumes, for each one. It takes a longtime, and it is too easy to make a mistake.

- The dilutions cover the range from 1/2 to 1/100 unevenly.In fact, the 1/2 vs. 1/3 dilutions differ by only 1.5-fold in concentration,while the 1/10 vs. 1/100 dilutions differ by ten-fold. If you are going tomeasure results for four dilutions, it is a waste of time and materialsto make two of them almost the same. And what if the half-maximal signaloccurs between 1/10 and 1/100? You won't be able to tell exactly where itis because of the big space between those two.

Serial dilutions are much easier to make and they cover the range evenly.

Serial dilutions are made by making the same dilution step over and over,using the previous dilution as the input to the next dilution in each step.Since the dilution-fold is the same in each step, the dilutionsare a geometric series (constant ratio between any adjacent dilutions).For example:

- 1/3, 1/9, 1/27, 1/81

- 1/5, 1/25, 1/125, 1/625

When you need to cover several factors of ten (several 'orders of magnitude') witha series of dilutions, it usually makes the most sense to plot the dilutions(relative concentrations) on a logarithmic scale. This avoids bunching mostof the points up at one end and having just the last point way fardown the scale.

Before making serial dilutions, you need to make rough estimatesof the concentrationsin your unknowns, and your uncertainty in those estimates. For example,if A280 says you have 7.0 mg total protein/ml, and you thinkthe protein could be anywhere between 10% and 100% pure, then yourassay needs to be able to see anything between 0.7 and 7 mg/ml.That means you need to cover a ten-fold range of dilutions, or maybe a bitmore to be sure.

If the half-max of your assay occurs atabout 0.5mg/ml,then your minimum dilution fold is(700mg/ml)/(0.5mg/ml) = 1,400.Your maximum is(7000mg/ml)/(0.5mg/ml) = 14,000.So to be safe, you might want to cover 1,000 through 20,000.

In general, before designing a dilution series, you need to decide:

- What are the lowest and highest concentrations (or dilutions)you need to test in order to be certain of finding the half-max? Thesedetermine the range of the dilution series.

- How many tests do you want to make? This determines the size of theexperiment, and how much of your reagents you consume. More tests will coverthe range in more detail, but may take too long to perform (or cost too much).Fewer tests are easier to do, but may not cover the range in enough detailto get an accurate result.

- What volume of each dilution do you need to make in order to haveenough for the replicate tests you plan to do?

Now suppose you decide that six tests will be adequate (perhapseach in quadruplicate).Well, starting at 1/1,000, you need five equal dilution steps (giving yousix total dilutions counting the starting 1/1,000) that end ina 20-fold higher dilution (giving 1/20,000). You can decide on a goodstep size easily by trial and error. Would 2-fold work? 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, 1/32. Yes, in factthat covers 32-fold, more than the 20-fold range we need. (The exact answeris the 5th root of 20, which your calculator will tell you is 1.82 foldper step. It is much easier to go with 2-fold dilutions and gives about thesame result.)

So, you need to make a 1/1,000 dilution to start with. Then you need toserially dilute that 2-fold per step in five steps. You could make 1/1,000 byadding 1 microliter of sample to 0.999 ml diluent. Why is that a poor choice?Because you can't measure 1 microliter (or even 10 microliters) accuratelywith ordinary pipeters. So, make three serial 1/10 dilutions(0.1 ml [100 microliters] into 0.9 ml): 1/10 x 1/10 x 1/10 = 1/1,000.

Now you could add 1.0 ml of the starting 1/1,000 dilution to1.0 ml of diluent, making a 2-fold dilution (giving 1/2,000).Then remove 1.0 ml from that dilution (leaving 1.0 ml for yourtests), and add it to 1.0 ml of diluent in the next tube (giving1/4,000). And so forth for 3 more serial dilution steps (giving1/8,000, 1/16,000, and 1/32,000). You end up with 1.0 ml of each dilution.If that is enough to perform all of your tests, this dilution planwill work. If you need larger volumes, increase the volumes you useto make your dilutions (e.g. 2.0 ml + 2.0 ml in each step).